The Barbican Centre exhibition shows how the Bauhaus as an avant-garde movement overcame the paradoxes between art and life.

It sure was an amazing experience to pass through the corridors of the Barbican building on my way to the Bauhaus exhibition since the architecture you are walking in is already full of the spirit created by those pioneers. “Bauhaus: Art as Life” is the most complete show held in he UK for more than 40 years about the German school that materialized the essence of Modernism from 1919 to 1933 and has its ideas influencing our lives up to now. Presenting over 400 works between paintings, furniture, architecture, film, textiles and many other artistic practices that combined formed the program of the school.

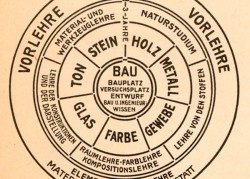

Those brutal blocks of concrete reflect the later developments based on the industrial tendency that dominated at the time. Even though it gives a rather cold feeling in the beginning Bauhaus had a more humanistic approach under the direction of Walter Gropius. The classes started with breathing exercises for relaxation instructed by Johannes Itten. From Monday to Saturday for the whole day students had classes that revolutionized the traditional patterns of the arts by then to develop a whole new avant-garde vision. They believed in the integration of art and life so they created pieces that would have incredibly visual appeal and at the same time be utilities for everyday use. The Bauhaus was the first institution to believe in the power of art to intervene and enhance practical life.

Paradoxically, it united institutionalism with avant-garde that was supposed to be against institutionalization. That was not the only paradox that the school was able to overcome. After 1923 there was a big shift into a more mechanical vision of society but some teachers like Paul Klee and Wassily Kandinsky kept the spiritual essence in the unitized vision. This monological vision that saw man as machines had in Kandinsky a practical formula exemplified in the exhibition by a questionnaire about primary forms and colours. For example, yellow for triangle, red for square and blue for circle. He believed in the universalism of forms. But then I ask myself, can’t the circle be red for someone else?

It is very impressive to be able to see the product of the union of all these great artists creating together for a common ideology. Can you imagine having Klee and Kandinsky as teachers? Later adding Mies van ver Rohe as well. Another proof of the paradoxes that Bauhaus overcame, because the original utopian vision of Gropius was transformed into an essentially mechanical production after 1923. But we can still find the union of machinery and spirituality like in Lászio Moholy-Nagy’s 1930 film “A Light Play” shown almost at the end of the exhibition that was presented in a chronological order. We can see the start of many styles like with free movement painting exercises that later developed into Abstract Expressionism.

For me it was a much better exhibition than the one I saw at Moma in 2009. At the Barbican one can feel the Bauhaus philosophy as a vehicle for the reconciliation of artists and machines as a positive answer for the barbarities of war. Even though they had a dualist/mechanical vision they held an organic/community network to share their ideology. It was a pity it had to end by 1933 with the anti-communist destruction of the Nazis. But its philosophy lived on influencing our lives up to now and some of the key original products will be at the Barbican Centre until August 12.